By Aderinsola Ajao

(As published in 234NEXT) January 23, 2011

Nothing better captures human history than a collection of information that is indelible and images that are everlasting. For many film enthusiasts, the moving picture medium does this best. However, within the medium, the differentiation between the purposes of the feature and the documentary film can not be overemphasised.

The essence of the documentary film and the documentary film maker takes the front stage at the iRepresent International Documentary Film Festival which ends today at Freedom Park.

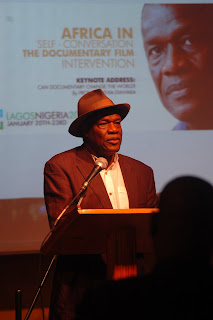

On the bill at the opening ceremony, held last Thursday, was Manthia Diawara’s keynote address ‘Can Documentary Change the World?’ Also showing was the film professor’s documentary, ‘Who’s Afraid of Ngugi?’

Spread the word

Linking African literature with the continent’s film culture, Diawara stressed the need for more public intellectuals like Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe and Nelson Mandela, who are renowned for their self-expression in spaces with global influence. In his words, these people had the genius of “having a place for their public intellectuals to express him or herself and to have that expression change the world.”

Heralding what would be a major pattern all through the day’s event, Diawara said maintaining and updating national and historical archives was a very important part of re-enforcing the African existence and was useful in presenting images and stories to the world that were true and positive of the continent. For him, the audience is home-based before it is global. “Films (should) have their legitimacy first in Africa,” he said. The problem with filmmaking in Africa, he said, is that, “We make films by addressing the West...in doing this, we betray a whole point of view...this is irrelevant in changing people’s lives here.”

He advised that filmmakers should learn to own Africa by first owning her myriad resources.

Presenting Diawara’s new publication, ‘African Film: New Forms and Aesthetics,’ managing director of the Nigerian Film Corporation (NFC), Afolabi Adesanya, supported the clamour for positive representations of Africa. The history of colonisation in Africa, he said, would not allow a European filmmaker make a movie that would be against his own. Adesanya asked the industry “to take ownership of their images” and stop making “films that put European audiences at their ease.” A trailer of the DVD accompanying the book was then shown.

Tribute

Three ‘film heroes past’ were honoured in a tribute. Veteran TV producer, diplomat and arts patron, Segun Olusola, was at hand to present plaques to Brendan Shehu, Tam Fiofori and Adegboyega Arulogun - all elder broadcasters who had contributed immensely to the progress of TV and documentary films in Nigeria.

Shehu, a former director of the NFC, was grateful for the award that he said showed efforts of his colleagues had not been in vain. For Arulogun, whom Olusola described as a teacher of documentary filmmaking, the honour was proof to upcoming filmmakers that “Nollywood was not created in a vacuum.” International collaborations were vital for Nollywood to grow, Arulogun said.

A painful experience

The audience’s joyous mood turned sober with the screening of Diawara’s documentary on the homecoming of Kenyan writer-activist, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, after 22 years in exile. Scenes in the movie took the audience through Ngugi’s early life to the Mau Mau struggle and its influence on current Kenyan politics. There were a lot of soul-thumping scenes, but none more moving than the sequence of shots that covered the attack on Ngugi’s family and the rape of his wife during his return to Kenya. Diawara himself admitted that it “was a painful film to make.”

Kiragu, co-ordinator of the couple’s trip to Kenya, was arrested alongside four others for the assault. The 84-minute film showed that there were mixed feelings for Ngugi and his activism in the East African country. There were a number of indispensable nuggets in the film such as Ngugi’s comment that, “identifying with another person’s language above your own is actually despising one’s self.”

For Ngugi, the film and its contents contributed “yet another way of liberating Africa,” according to Diawara, the film’s narrator, writer and director.

The programme returned from recess to expound on issues of identity, consciousness and logistics in documentary film making in a workshop session titled ‘Redeeming the African Image: A case for African Documentary Films.’

Moderator of the session was Emeka Mba, director-general of the Nigerian Film and Video Censors Board with the panel boasting Senegalese, Lydie Diakhate; Joke Silva, Mahmoud Ali-Balogun and Jaiye Ojo.

Improving the art

During the workshop, Diakhate, a film producer and festival organiser, said, it was “crucial to have a platform to be able to show new images of Africa.” She accentuated the presence of positive stories that can be told about the continent and hailed festivals as medium for encouraging co-operation, sharing experiences and improving production quality amongst filmmakers.

On his part, Ali-Balogun posed the question of what exactly a filmmaker sets out to achieve with a documentary. Speaking personally, he said most of his documentaries are advocacy tools meant for improving Nigeria. As a patriotic movie maker, he would not peddle negative images of his country for any reason. This, he said, was mostly impossible for those who sourced their funds from abroad and had to ‘dance to the tune’ of their sponsor.

In light of the challenges facing those already established in the genre, the lot fell on Ojo to allay the fears of aspiring filmmakers. Speaking in a deservingly upbeat tone, he said there are avenues for surviving in the trend despite a seemingly high frustration rate.

Joke Silva also said that more skill acquisition centres were crucial to honing the talent of the industry’s up and coming producers.

There was a slight argument over how easy it was to shoot a documentary, but it was agreed that the industry’s green horns should not see their task as daunting but something that has to be done if the passion was there.

The moderator, Mba summed it up by saying that the overall duty for filmmakers is to “tell our stories in a more socially-responsible way.”

Doing this effectively were the two other films on the event’s bill. Olu Holloway’s ‘Slum Sweeper’ was an exposé on the construction of the Second Mainland Bridge, widely known as the Eko Bridge.

The festival film, Jihan El-Tahri’s ‘Behind the Rainbow,’ a documentary on South African politics, closed the evening’s schedule at Terra Kulture.

www.irepfilmfestival.com

3 Oguntona Crescent, Gbagada Phase 1, Lagos Nigeria.

P.O. Box 36 Surulere.

T: +234 803 425 1963, +234 802 201 6495, +234 803 403 0646

E: info@irepfilmfestival.com

No comments:

Post a Comment